Please scroll down for english version

Entrevista completa para Noorderlicht Photofestival Magazine

Publicada en Mundos Creados, Noorderlicht Photofestival 2002:

https://www.noorderlicht.com/en/programma/fotomanifestatie-2002-mundos-creados/

Illand Pietersma: Soy crítico de arte, fotografía, jazz y worldmusic. Trabajo principalmente para un periódico regional del norte de los Países Bajos y algunas otras revistas. Desde hace 15 años, varios fotógrafos de América Central empezaron a trabajar más libremente y a experimentar con la imagen, materiales y técnicas. Parece una especie de ruptura colectiva con el pasado en esa parte del mundo. ¿Puede explicar qué ha sucedido? ¿Y cómo ha podido ocurrir en más países al mismo tiempo? Quizá tenga que ver con los conflictos armados y guerras intestinas en varios países de Centroamérica y América Latina. ¿Habra esto afectado también en Costa Rica o hay otras circunstancias? ¿Puedes hablarnos sobre la historia de la foto en Costa Rica?

Jorge Albán-Dobles: Pienso que la percepción de ruptura colectiva se debe a una combinación de conciencia internacional y cambios provocados por las tendencias hacia una sociedad mundial de la información más que por las condiciones locales. Adrián Valenciano es un fotógrafo costarricense que produjo una importante obra a finales de los años sesenta. Publicó libros y estableció un estilo documental interpretativo (cercano a William Klein y Robert Frank). Sin embargo, como el intercambio de información en aquellos años era básicamente unidireccional (del centro a la periferia) es un completo desconocido fuera de Costa Rica.

Yendo más atrás en el tiempo, tenemos la obra fotográfica de Max Jiménez, uno de los artistas costarricenses más valientes de las primeras décadas del siglo XX. Cuando casi todo el mundo era partidario de una estética nacionalista, él se volvió modernista y, gracias a sus frecuentes viajes, se hizo compañía de gente como Tarsila Do Amaral. Escribió poesía y prosa, pintó y dibujó, y su obra fotográfica era poco conocida, incluso en Costa Rica, hasta que hace un par de años el Museo de Arte Costarricense le dedicó una gran retrospectiva. Sus fotografías de edificios y calles de principios del siglo XX evidencian un gran avance perceptivo, que recuerda a las imágenes más rigurosas de Alfred Stieglitz, y sin embargo su obra nunca fue comprendida ni reconocida, y finalmente se suicidó. Nuestra historia está llena de avances, sorprendentes, conmovedores, inspiradores, pero hasta hace poco practicamente anónimos y a menudo trágicos.

Illand Pietersma: ¿Hacías tú mismo otro tipo de fotografías hace algún tiempo? En caso afirmativo, ¿por qué decidiste hacer tu fotografía actual, más libre y escenificada? ¿Cuál es la principal diferencia entre tus obras anteriores y las recientes?

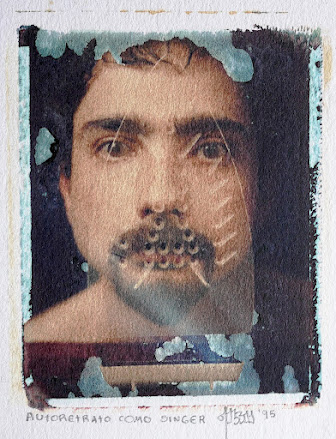

Taxi Año desconocido, plata y gelatina sobre chatarra automotriz,1995

Jorge Albán-Dobles: Entre 1996 y 1999 intervine piezas de carros chocados con autorretratos desnudo sosteniendo a mi hija pequeña. La mayoría de los espectadores se sentían perturbados por la interacción entre el metal filoso y los cuerpos desnudos, y muchos buscaban inconscientemente formas de no enfrentar dichas cuestiones, concentrándose en la técnica. Me preguntaban: "¿Cómo lo has hecho? Y al principio yo caía en la trampa y contaba todos los detalles anecdóticos de cómo localizaba cada pieza en los cementerios de chatarra automotriz, lijaba y sellaba la superficie para la emulsión líquida fotográfica, etc... La retórica del dolor era tan fuerte en esas piezas que el espectador se sentía amenazado. El lenguaje corporal era una referencia a las imágenes de la Vírgen María con el Niño Dios. Yo suplantaba su cuerpo, pero todo el lenguaje visual seguía siendo muy masculino y agresivo.

En mi siguiente grupo de obras, los Monólogos Imposibles, que traje a Noorderlicht, utilicé un lenguaje fotográfico aparentemente transparente, para que la gente no viera el medio, sólo el tema, como hacen cada vez que reciben fotos del laboratorio fotográfico. De este modo, también me distanciaba de todo el dolor barroco y la retórica sangrante de la estética del "fotógrafo latino" que, a mi parecer, nos está llevando a un callejón sin salida.

Nos Fregamos..., foto analógica en tinta pigmentaria, 2001 (versión Noorderlicht)

IP: ¿Podrías contarnos algo sobre tus antecedentes y tu vida? ¿En tu opinión, cómo se relaciona con tu fotografía?

JA: Cuando por fin obtuve algo de estudios formales de fotografía a los 16 años, ya llevaba tres años ampliando mis propias fotografías en laboratorio casero. De regreso a Costa Rica en 1991 había pasado más de la mitad de mi vida viviendo fuera del país. El desarraigo y la transculturación son cosas naturales para muchos centroamericanos. Sea por razones políticas, económicas o culturales, no dejamos de movernos. Centroamérica y el Caribe siempre han sido un paso de norte a sur y de un océano a otro. Nuestra naturaleza es híbrida y difícil de aprehender, su hechura siempre en proceso. Y así es nuestro arte y nuestra fotografía.

IP: En su serie "Monólogos imposibles" combina la "fotografía doméstica" con textos inconexos. ¿De dónde proceden los textos? ¿Te los has inventado o son de libros, periódicos, revistas, etc.?

JA: Todo viene de la vida. Como dijo Pablo Casals: "La música debe ser parte de algo más grande que ella misma, parte de la vida". Huyo del historicismo de moda porque no quiero discriminar a mi público de entrada. Me parece un reto reimaginar lo rutinario y utilizarlo para establecer conexiones con los arquetipos que nos mueven. Los textos de la serie Monólogos Imposibles estan tan vivos y orgánicos como nosotros. Cada vez que los escribo cambio algo. Nunca los he escrito dos veces iguales.

IP: ¿Por qué quiere añadir una capa más a sus obras fotográficas con los textos? ¿No son las fotografías en sí mismas lo suficientemente alienantes? - Inviertes los roles domésticos tradicionales: el hombre lava los platos, arregla la ropa, plancha y satisface a la mujer, ya que tradicionalmente es la mujer la que hace esas cosas. El hombre también parece un poco "torpe": se corta afeitándose y cose mal el botón de su camisa, incluso con ella puesta ¿Qué dice esto sobre los modelos de conducta en Costa Rica, el mundo latino u "occidental"?

JA: Algunas imágenes son alienantes, pero las obras van mucho más allá del género y la alienación. El texto está ahí para desafiar nuestras percepciones de lo que un texto debe hacer a una imagen, no solo guiarla como en periódicos y anuncios. A algunos de mis amigos, fotógrafos en el sentido clásico, les desanima que no exista una conexión racional (o de hemisferio izquierdo) entre texto e imagen. El vínculo hay que encontrarlo a través de los sentidos. Las piezas tratan de flujos de pensamiento desencadenados por los sentidos y constreñidos por un arquetipo social masculino poco explorado.

IP: Tu fotografía no parece muy "latina". Muchos otros fotógrafos del "Gran Caribe" se sumergen en sus raíces culturales. Tu trabajo parece muy moderno y europeo. ¿Podría explicar por qué? ¿Tiene que ver con su educación en España, Israel y Nueva York? ¿Se inspira en fotógrafos europeos o estadounidenses?

JA: América Latina ha llegado a donde está, en gran medida, debido a un arquetipo social masculino muy destructivo. Evito intensamente interpretar al "buen salvaje" o reforzar cualquier idea errónea de lo que es o debería ser un país en desarrollo. Aunque aprecio mucho algunos de los trabajos recientes de otros fotógrafos centroamericanos, creo que muchas de sus imágenes caminan por una línea peligrosamente delgada entre la exploración y la explotación. La familia de mi padre vino de Colombia hace cinco generaciones, todos son de piel clara y él jura que el apellido Albán proviene de Irlanda. La familia de mi madre, en cambio, son en su mayoría judíos conversos españoles de piel oscura que escaparon de la Inquisición y llegaron de Cuba en el siglo XVII. Como puede ver, después de todo, quizá esté explorando mis raíces culturales...

IP: ¿Cuál es, en su opinión, la posición de la fotografía contemporánea costarricense/centroamericana en el "mapa mundial de la fotografía"?

JA: Uno de los primeros productos fotográficos latinoamericanos fueron las cartes de visite con imágenes de indígenas. Creo que ha llegado el momento de avanzar. De tratar temas contemporáneos relevantes de manera imaginativa que no encasillen nuestra cultura como "mágica" o "fantástica", como se ha hecho desde hace más de cinco siglos. La fotografía centroamericana ha avanzado mucho en este sentido. Ahora tenemos una generación de fotógrafos mucho mejor informados y preparados. Costa Rica en particular siempre ha sido un paraíso para la gente que quiere alejarse de la opresión, ya fuera de la Corona Española del Siglo XVI o la guerra actual en Colombia. Costa Rica siempre ha acogido inmigrantes, muchos de ellos por motivos políticos. Somos una cámara de mezcla cultural privilegiada y ahí radica nuestro potencial como capital cultural.

IP: ¿Cree que existen muchas diferencias o similitudes con la fotografía europea y/o americana? ¿Cuáles podrían ser? ¿Cómo crees que se desarrollará la fotografía en Costa Rica/Centroamérica en el futuro?

JA: Los artistas del tercer mundo o postcoloniales son aún más importantes que los artistas del primer mundo desarrollado. ¿Cómo es esto posible? Por la misma razón por la que de noche la luna es mucho más importante que el sol... porque entonces se necesita más luz. Las fuerzas homogeneizadoras culturales son tan astutas hoy en día que no se puede resistir a la corriente dominante, como se podía hace unas décadas. Ahora incluso nos dice cómo ser alternativos y no convencionales. Como fotógrafos artistas del Tercer Mundo tenemos la responsabilidad de interferir en los códigos de dominación cultural. Numerosos fotógrafos y fotógrafas centroamericanas lo están haciendo. Están desafiando las expectativas de lo que la fotografía centroamericana puede ser y aportar al mundo del arte

Follows full english version ( ORIGINAL):

Interview for Noorderlicht Photofestival Magazine

Part of Mundos Creados, Noorderlicht Photofestival 2002

https://www.noorderlicht.com/en/programma/fotomanifestatie-2002-mundos-creados/

Illand Pietersma: I am a critic of art, photography, jazz and worldmusic. I mainly work for a regional newspaper in the north of the Netherlands and some other magazines. Since about 15 years ago several photographers in Central-America began to make free work and started to experiment with image, material and technices. There seems to have taken place a kind of collective break with the past in that part of the world. Can you explain what has happened? And how could it happen in more countries in the same time? Maybe it has to do with the geurilla- and civil wars in several countries in Central- and Latin America. Has Costa Rica been affected by these or are there other circumstances? Can you tell us about the main history of photography in Costa Rica?

Jorge Alban-Dobles: I think such perceived collective break comes from a combination of international awareness and changes brought about by the trends towards a world information society more than local conditions. Adrian Valenciano is a Costa Rican photographer that produced an important body of work at the end of the sixties. He published books and established an interpretative documentary style (close to William Klein and Robert Frank). However as the exchange of information in those years was basically unidirectional (from center to periphery) he is a complete unknown outside Costa Rica. Going further back in time, we have the photographic work of Max Jimenez, one of the most courageous costarican artists from the first decades of the the 20th century. When almost everyone favored a Nationalist Aesthetic he turned Modernist and through his frequent travels kept the company of people like Tarsila Do Amaral. He wrote poetry and prose, produced painting and drawing, and his photographic works were little known,even within Costa Rica, until a couple of years ago the Museum of Costa Rican Art produced a major retrospective on him. His photographs of building and streets from the beginning of the 20th Century evidence a major perceptual breakthrough, reminiscent of the most rigurous Alfred Stieglitz images, yet his work was never understood nor recognized, and eventually committed suicide. Our history is full of breakthroughs, amazing, moving, inspiring, yet until recently anonymous, and even tragic, breakthroughs.

IP: Did you, yourself, make an other kind of pictures some while ago ? If yes, why did you choose to make your current, more free and staged photography? What is the main difference between your earlier and your recent photo-works?

JAD: Between 1996 and 1999 I intervened crashed car pieces with nude self portraits holding my newborn girl. Most viewers felt disturbed by the interaction between the torn metal and body parts and many found a way out of having to deal with such issues by concentrating on technique. They would ask – How did you do it? And at first I would fall for it and tell all the anecdotal details of how I located each piece in car cemeteries, prepared the surface for the photographic liquid emulsion and so on… The rethoric of pain was so strong in such pieces that the spectator felt threatened.. The body language was a reference to images of the madonna with holy child. I was supplanting her body but all the visual language was still very masculine and aggressive. In my next group of works, the Impossible Monologues I used a seemingly transparent photographic language, so people wouldnt see the medium, only the subject matter as they do every time they pick photos from the lab. Doing so I also distanced myself from all the barroque pain and bleeding heart rethoric of the “latin photographer” aesthetic, which I believed to be nearing a dead-end.

IP: Could you tell something about your own backgrounds and life? How does it relate to your photography in your own opinion?

JAD: By the time I got some formal photo studies by age 16 I had been already printing my own photos for three years. When I returned to Costa Rica in 1991 I had spent over half of my life living outside this country. Uprooting and transculturation are natural things for many Central Americans. Be it for political, economic or cultural reasons, we keep moving. Central America and the Caribbean have always been a passage from north to south and from one ocean to the other. Our nature is hybrid and hard to grasp, its making always in process. And so is our art and our photography.

IP: In your series 'Impossible Monologues' you combine 'domestic photography' with unrelated texts. Where do the texts come from? Did you make them up, or are they from books/papers/magazines/etc. ?

JAD: It all comes from life. As Pablo Casals once said “Music must be a part of something larger than itself, a part of life” I shy away from trendy historicism as I don’t want to start out discriminating my audience. I find it a challenge to picture the rutinary and use it to establish connections with the archetypes that makes us tick. The texts from the Monologues are as alive and organic as I am. Every time I write them I change something. I have never written them the same twice.

IP: Why do you want to put an extra layer in your photoworks, adding the texts? Aren't the photographs on themselfs not alienating enough? - Because you also seem to turn around the traditional domestic roles: the man washes the dishes, repairs clothes, irons and satisfys the woman - as traditionally it is the woman who does such things. The man also seems a bit 'clumsy': he cuts himself shaving and sews a button on a shirt, still wearing the same shirt. What does it say about role-models in Costa Rica/the Latin World/or the 'western' world?

JAD: Some images are alienating, but the works are about a lot more than gender and alienation. The text is there to challenge our perceptions of what a text should do to an image (as in newspapers or advertisements). Some of my friend photographers in the traditional sense were put off by the fact that there is no rational left-brain connection between text and image. The link is to be found through the senses. The pieces deal with flows of thought triggered by the senses and constrained by a seldom explored male social archetype.

IP: Your photography doesn't look very 'Latin'. Many other photographers from the 'Wider Caribbean' dive into their cultural roots. Your work looks very modern and European. Could you explain why? Does it have to do with your education in Spain, Israel and New York? Are you inspired by European or American photographers?

JAD: Latin America got itself where it is, to a great degree, due to a very destructive male social archetype. I intently avoid playing the “good savage” or reinforcing any misconceptions of what a developing country is or should be. Even thought I appreciate very much some of the recent work produced by fellow central american photographers, I believe a lot of their images walk a dangerously thin line between exploration and exploitation. My fathers family came from Colombia five generations ago, they are all fair skinned and he swears the Alban family name originates from Ireland. My mothers family are mostly dark skinned Spanish jewish converts that escaped the Inquisition and arrived from Cuba in the seventeenth century. As you can see maybe I am diving in my cultural roots after all...

IP: What is in your view the position of Costa Rican/Central-American contemporary photography on the 'world-map of photography'?

JAD: One of the first Latin American photographic products were carte-de-visites with images of indigenous people. I think it is time to move on. To deal with relevent contemporary subject matter in imaginative ways that do not pigeonhole our culture as “magic” or “fantastic”, the same way it has been done for over five centuries now. Central American photography has come a long way in this sense. We now have a generation of photographers who are better informed and prepared than ever. Costa Rica in particular has always been a heaven for people wanting to get away from oppression, be it the Sixteen Century Spanich Crown or the ongoing war in Colombia. Our country has always embraced immigrants, many of them for political reasons. We are a privileged cultural mixing chamber and here lays our potential as a cultural capital.

IP: Do you think there are many differences or similarities with European and/or American photography? What could they be? How do you think the photography in Costa Rica /Central America will develop in the future?

JAD: Third world or post colonnial artists are even more important than artists in the first, developed world. How can that be so? For the same reason at night the moon is so much more important than the sun… because more light is needed then. Cultural homogenizing forces are so strong nowadays that the mainstream can not be resisted, as it could a few decades ago. Now it even tells us how to be alternative and non-mainstream! As third world artist photographers we have the responsibility of jamming the cultural domination codes. Several Central American photographers are are doing just that. They are challenging the expectations of what Central American photography can be and add to the Art World.

No hay comentarios.:

Publicar un comentario

Gracias por comentar. Te recordamos que no se vende ni distribuye nada. El fin es educativo 100%